Two nil down and facing the prospect of a second successive away whitewash, whilst once again being both out batted and out bowled (save for James Anderson) by Australia, it’s clear that something needs to change for England in the Ashes.

Given the injuries to Toby Roland-Jones, Steven Finn and Mark Wood, the travails of England’s bowling arguably couldn’t be helped but England’s batting problems are arguably harder to explain away beyond the simple point that the quality doesn’t exist. When only four of your batting picks average 40+ in first class cricket (and you clearly don’t trust one of them in Gary Ballance), you can’t expect the personnel to average much more in Test Cricket and thus put up sufficient scores to win games. Which then brings us to the question that England ought to be asking of themselves as they seek to get back into this series: Do we need to pick Bairstow purely as a batsman?

The reality is that for anyone who has followed County Cricket over the last four years, Bairstow is a giant in terms of domestic batsmen. His returns for Yorkshire dwarf anyone else in the County game including some hugely big names. Over the last three years his form has been nigh on ridiculous whenever he’s stepped back into the County ranks, topping the averages with an average of 82 and a century percentage of 35% (plus a healthy conversion rate). The below table highlights the leading run scorers over the last three years in County Cricket (minimum innings 20) and Bairstow averages over 15 more per innings than his closest rival.

| Batsmen (Min 20 inns) | Inns | Runs | Ave | SR | 50s | 100s | Conv | Cent% |

| JM Bairstow | 20 | 1649 | 82.45 | 0.79 | 5 | 7 | 1.40 | 35.00% |

| AG Prince | 22 | 1478 | 67.18 | 0.68 | 5 | 5 | 1.00 | 22.73% |

| AN Cook | 22 | 1445 | 65.68 | 0.53 | 4 | 6 | 1.50 | 27.27% |

| KC Sangakkara | 54 | 3400 | 62.96 | 0.67 | 10 | 14 | 1.40 | 25.93% |

| SA Northeast | 61 | 3522 | 57.74 | 0.64 | 16 | 9 | 0.56 | 14.75% |

| RN ten Doeschate | 49 | 2648 | 54.04 | 0.67 | 17 | 5 | 0.29 | 10.20% |

| AC Voges | 24 | 1241 | 51.71 | 0.53 | 8 | 2 | 0.25 | 8.33% |

| BM Duckett | 59 | 2988 | 50.64 | 0.77 | 10 | 11 | 1.10 | 18.64% |

| JWA Taylor | 20 | 991 | 49.55 | 0.57 | 5 | 2 | 0.40 | 10.00% |

| LS Livingstone | 33 | 1618 | 49.03 | 0.58 | 9 | 4 | 0.44 | 12.12% |

| S van Zyl | 21 | 1023 | 48.71 | 0.52 | 4 | 2 | 0.50 | 9.52% |

| AD Hales | 30 | 1459 | 48.63 | 0.66 | 4 | 4 | 1.00 | 13.33% |

| AN Petersen | 43 | 1995 | 46.40 | 0.62 | 7 | 6 | 0.86 | 13.95% |

| MJ Cosgrove | 76 | 3484 | 45.84 | 0.64 | 15 | 11 | 0.73 | 14.47% |

| RJ Burns | 70 | 3204 | 45.77 | 0.51 | 20 | 5 | 0.25 | 7.14% |

| WL Madsen | 65 | 2974 | 45.75 | 0.55 | 14 | 9 | 0.64 | 13.85% |

| T Westley | 56 | 2560 | 45.71 | 0.54 | 13 | 6 | 0.46 | 10.71% |

| CDJ Dent | 71 | 3199 | 45.06 | 0.50 | 20 | 8 | 0.40 | 11.27% |

| JL Denly | 65 | 2921 | 44.94 | 0.55 | 16 | 7 | 0.44 | 10.77% |

| GJ Bailey | 20 | 894 | 44.70 | 0.59 | 5 | 3 | 0.60 | 15.00% |

He also had one of the great County seasons in recent years in 2015 (though second only to Sangakkara’s epic 2017 in terms of recent efforts) as the below table of top 10 highest County season averages (min 8 matches) indicates:

| Player | Mat | Runs | Ave | Year |

| KC Sangakkara | 10 | 1491 | 106.5 | 2017 |

| MR Ramprakash | 14 | 2211 | 105.28 | 2006 |

| MR Ramprakash | 15 | 2026 | 101.3 | 2007 |

| NRD Compton | 11 | 1191 | 99.25 | 2012 |

| NV Knight | 10 | 1520 | 95 | 2002 |

| DJ Hussey | 12 | 1219 | 93.76 | 2007 |

| JM Bairstow | 9 | 1108 | 92.33 | 2015 |

| SG Law | 16 | 1820 | 91 | 2003 |

| MR Ramprakash | 11 | 1350 | 90 | 2009 |

| MEK Hussey | 14 | 1697 | 89.31 | 2003 |

And of the active England eligible players (if we ignore the bloke the ECB ask us to) he is the only one with a 50+ average in County Cricket (min 20 innings).

| Batsmen (min 20 inns) | Sum of Runs | Ave |

| KP Pietersen | 5031 | 59.89 |

| JM Bairstow | 5937 | 51.63 |

| LS Livingstone | 1618 | 49.03 |

| ME Trescothick | 13729 | 48.51 |

| AN Cook | 6465 | 47.54 |

| GS Ballance | 5396 | 47.33 |

| JE Root | 2679 | 47.00 |

| NLJ Browne | 3831 | 44.03 |

| BM Duckett | 3748 | 43.58 |

| JM Clarke | 2656 | 43.54 |

| RJ Burns | 5711 | 42.30 |

| DW Lawrence | 2072 | 42.29 |

| IR Bell | 8174 | 42.13 |

| RS Bopara | 8844 | 41.52 |

| NRT Gubbins | 2317 | 41.38 |

| JC Hildreth | 13344 | 41.19 |

| H Hameed | 1968 | 41.00 |

| CT Steel | 899 | 40.86 |

| WL Madsen | 8602 | 40.58 |

| NRD Compton | 9186 | 40.47 |

So, as we can see. of all the options available to England in terms of batsman to bring in, no-one even comes close to matching Bairstow in terms of output. If this scenario feels familiar, it’s probably because it mirrors the same such debates England were having in the mid 90’s about Alec Stewart and the wicket-keeper position.

Which then brings us on to what are the downsides?

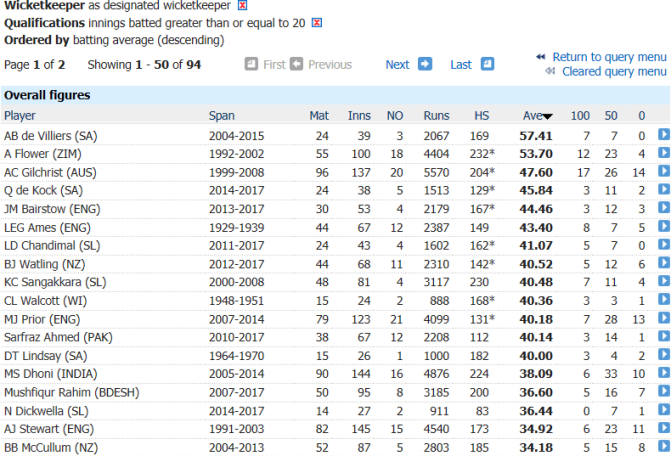

Firstly Bairstow himself doesn’t want to do it and is committed to keeping for England, which is understandable given his keeping improvements over the last two years and the obvious kick he gets from being the focal point in this team. Yet there is a point where England management need to intervene and point out that to truly fulfil his potential greatness as a batsman and help England where their need is greatest, Bairstow ought to drop the gloves. Few wicket-keeper batsmen thrive in Test cricket if their top order cannot post scores (see Quinton De Kock for South Africa this summer gone). England need Bairstow the batsman to make this happen. Plus, unlike for England in the 90s, England have a mean batsman in Ben Foakes as their backup keeper. He may potentially be the best keeper in the world, but he also averages 40+ himself over the last three years in County Cricket.

Secondly, Bairstow’s Test form as a batsman alone is patchy. Which is a fair point

| Grouping | Span | Mat | Runs | HS | Bat Av | 100 | Wkts | BBI | Bowl Av | 5 | Ct | St |

| Keeper | 2013-2017 | 30 | 2179 | 167* | 44.46 | 3 | – | – | – | – | 113 | 7 |

| Not Keeper | 2012-2015 | 17 | 753 | 95 | 28.96 | 0 | – | – | – | – | 10 | 0 |

Yet Jason Gillespie in 2015 remarked that a key part of his form turnaround was based on allowing Bairstow to dictate his technique and avoiding confusion in his approach.

In reality, given these considerations, the likeliest option available is a move up the order to 5 enabling Bairstow to keep and bat higher up the order (as he does very well for Yorkshire). Yet few keepers in Test history have combined excellent top to middle order batting, particularly in a struggling team, which suggests Bairstow could always be slightly compromised by two roles.

Ultimately given the situation in the series, although there are risks and England will be reluctant to disrupt their fielding and batting by changing their keeper halfway through an Ashes series, desperate times call for desperate measures. With quality batsmen lacking, England should be thinking hard about giving one of their best ones every chance to shine.

Postscript – Mark Butcher eloquently states the case for this move here. It’s worth a listen.